|

By guest blogger: Katey Duffey

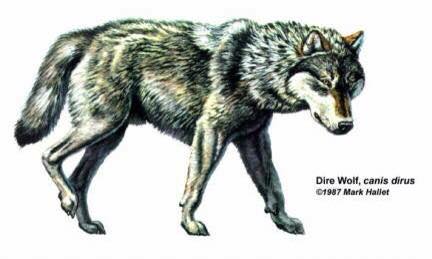

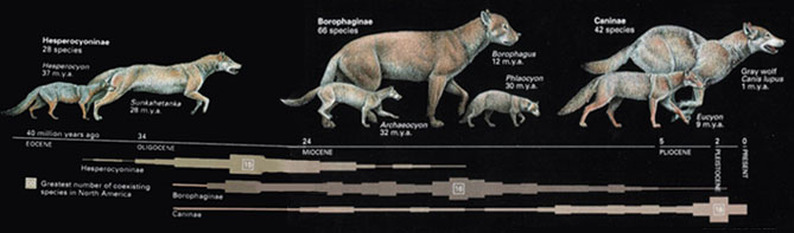

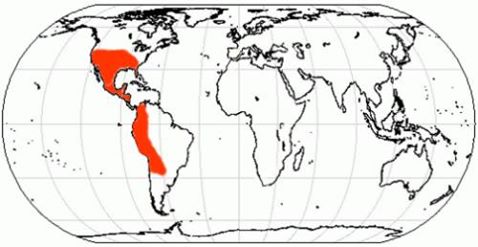

The Rise and Fall of North America’s Large Wolves (Mid-Late Pleistocene: Rancholabrean Age) Following a pre-historic, wolf-like species called Canis ambrusteri were three large wolf-like species. In South America, C. gezi and C. nehringi appeared, while C. dirus evolved in North America during the late Pleistocene. Contrary to popular belief, the modern grey wolf did not evolve from the dire wolf. It evolved in Eurasia from a different wolf-like ancestor, most likely C. mosbachensis, before crossing the Bering Strait land-ice bridge. The dire wolf is often described as being a more robust version of the modern wolf. It had a broader and thicker skull, deep jaws, and massive teeth with enlarged carnassials. Many researchers suggest that dire wolves had substantial bone crushing power comparable to that of hyenas. This, coupled with their shorter, stockier limbs, indicates a possible scavenging behavior as a method of feeding. However, in areas of more tropical habitats, dire wolves would have been more of a pursuit-predator, hunting Bison, Equus and camelids. The evolution of the dire wolf is considered to be one of the most dramatic events for the genus Canis. It appeared fairly suddenly in evolutionary terms, and was not only the largest Canis species, but had larger populations than any other members of the genus. This includes extant (still living) members. It is also the most common fossil of a canid throughout North America. It survived between 130,000-10,000 years ago during the end of the Rancholabrean period of the late Pleistocene and the beginning of the Holocene epoch. Fossils have been found in over 100 sites, with several sites in South America as well. Southern Alberta, Canada is estimated to be the most northern locality of the occurrence of dire wolves, though some argue those remains belong to early gray wolves. Meanwhile, southern Bolivia is the furthest southern locality. Presently, there are 10 Mexican locations of fossil records. These southern records include the ancestor C. ambrusteri, as well as C. gezi and C. nehringi within tropical deposits. Regardless of its exact range, dire wolves became extinct approximately 8,000 years ago, along with the megafauna of the late Pleistocene. During the era of dire wolves, Cope’s rule applied. Cope’s rule is the development of larger sized bodies, which is a result of enhancing the ability to capture large prey and avoid predators. It also helps improve thermal efficiency and reproductive success in cooler climates. Predator size is correlated with alterations of prey size. North America is documented as having some of the largest land mammals between the late Pleistocene and early Holocene. This trend can be responsible for the extinction of a species as well, especially mammals. Another possibility is that dire wolves could not compete with the leaner, swifter red wolf and grey wolf to pursue the increasingly smaller, more agile prey species dominating the ecosystem. It is also possible that it was out competed by the arrival of human hunters for larger prey. References

Anyonge, W. & Baker, A.(2006). Craniofacial morphology and feeding behavior in Canis dirus, the extinct Pleistocene dire wolf. Journal of Zoology, 269: 309-316. Garrido, G. & Arribas, A.(2008). Canis accitanus nov. sp., a new small dog (Canidae, Carnivora, Mammalia) from the Fonelas P-1 Plio-Pleistocene site (Guadix basin, Granada, Spain). Geobios, 41: 751-761. Hodnett, J.P.M., Mead, J.I. & Baez, A.(2009). Dire wolf, Canis dirus (Mammalia; Carnivora; Canidae), from the late Pleistocene (Rancholabrean) of East-Central Sonora, Mexico. The Southwestern Naturalist, 54(1): 74-81. Nowak, R.M.(2003). Wolf Evolution and Taxonomy. In Wolves: Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation. Mech, L.D. & Boitani, L. (eds), University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL, pp. 240-248, 356-357. Sotnikova, M. & Rook, L.(2010). Dispersal of the Canini (Mammalia, Canidae: Caninae) across Eurasia during the late Miocene to early Pleistocene. Quaternary International, 212: 86-97. Van Valkenburgh, B., Wang, X. & Damuth, J.(2004). Cope’s rule, hypercarnivory, and extinction in North American canids. Science, 306: 101-104. Wang, X. Tedford, R. Van Valkenburgh, B. & Wayne, R.(2007). Evolutionary history, molecular systematics,and evolutionary ecology of Canidae. In The Biology and Conservation of Wild Canids. Macdonald, D. & Sillero-Zubiri, C. (eds), Wildlife Conservation Research Unit, University of Oxford, pp.39, 45-53.

2 Comments

Lindsey

3/15/2015 08:17:31 pm

LOVE the science behind the cinema idea! Very cool! Really great read.

Reply

Ramiro

3/20/2017 05:33:05 pm

Hola Katey, creo haber hallado una huella de canis dirus en la Patagonia Argentina, provincia de santa cruz, es una roca fosilizada con la huella, si puedo enviarte una foto quizás me sepas decir de que se trata, gracias. Ramiro Torres

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Blog Archive

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed