Purring spider (Image: Alex Sweger/University of Cincinnati) Purring spider (Image: Alex Sweger/University of Cincinnati)

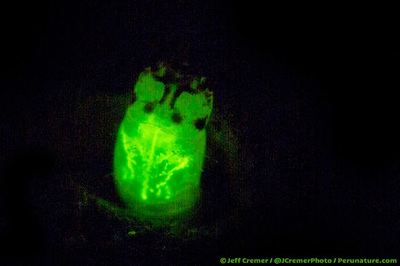

The purring wolf spider, it's music. For the first time, a spider has been recorded producing what appear to be audible courtship signals over and above pure vibrations. Many spider species rely heavily on vibrations to send signals to one another, by shaking leaves or strands of their webs.

Uetz and Sweger found that males produce the sound and only females respond to a played recording of the purr, suggesting that the purr is used in courtship. The males only produce the sounds if they are standing on something that will vibrate, like a leaf, and females only respond when perched on a similar surface. They think that the signal reaches the female by travelling as sound in air, which causes the leaves a female is standing on to vibrate. The purring spiders may help us better understand how communication by sound first evolved. Their findings were reported today at the annual meeting of the Acoustical Society of America in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Sorce: newscientist.com El ronroneo de la araña lobo, es música. Por primera vez, una araña ha sido registrada produciendo lo que parece ser señales de cortejo audibles por encima de puras vibraciones. Muchas especies de arañas dependen en gran medida las vibraciones para enviar señales a la otra, por agitación de hojas o hebras de sus telas. Uetz y Sweger encontraron que los machos producen el sonido y sólo las hembras responden al ronroneo, lo que sugiere que el ronroneo se utiliza en el cortejo. Los machos sólo producen los sonidos si están de pie sobre algo que va a vibrar, como una hoja, y las hembras sólo responden cuando están paradas en una superficie similar. Ellos piensan que la señal llega a la hembra viajando como sonido en el aire, lo que provoca que la hoja donde se encuentra parade la hembra vibre. El ronroneo de estas arañas pueden ayudarnos a entender mejor cómo la comunicación por sonido evolucionó. Sus resultados fueron publicados hoy en la reunión anual de la Sociedad Americana de Acústica en Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Fuente: newscientist.com Click here to listen to the spider

0 Comments

Photos: BTech

The first 21 days of a bee’s life are captured in this inspiring video by photographer Anand Varma. Bees pollinate 1/3 of the world’s food crop but are being threatened by the Varroa destructor mite; Varma was hired to document the process. Scientists have learned to breed mite-resistant bees which they are now trying to introduce into the wild. In an attempt to better understand exactly what happens as a bee grows from an egg into an adult insect, photographer Anand Varma teamed up with the bee lab at UC Davis to film the first three weeks of a bee’s life in unprecedented detail, all condensed into a 60-second clip. The video above presented by National Geographic doesn’t include commentary, but Varma explains everything in a TED talk. The primary goal in photographing the bees was to learn how they interact with an invasive parasitic mite that has quickly become the greatest threat to bee colonies. Source: thisiscolossal.com By guest blogger: Katey Duffey  Image: awoiaf.westeros.org Image: awoiaf.westeros.org In the “Lands of Ice and Fire”, the most important member of the world’s bestiary is perhaps the raven. It is said that the Children of the Forest taught the First Men to use ravens for a means of long distance communication. Those with gifts for prophetic visions and nature-based powers, the greenseers, could skinchange into ravens to communicate with people far away. Bran Stark is visited by the unusual three-eyed raven in his dreams, which guides him to a certain place to learn of his destiny. The ravens of Westeros are similar to real world ravens, except they are stronger and are more skilled at homing. They can also imitate human speech. Most ravens are trained to fly to only one location, but highly prized birds can be trained to fly to multiple locations to carry messages. White ravens from the Citadel are rare occurrences that mark the changing of seasons.  Raven, Photo: www.allaboutbirds.org Raven, Photo: www.allaboutbirds.org The common raven (Corvus corax) is part of the family Corvidae in the Passeriformes order that includes 120 species such as crows, magpies, jackdraws and jays. Ravens are large, black birds standing between 55-68cm (22-27in). They differ from crows in that they have a wedge-shaped tail, a heavier, longer bill, and thick, shaggy throat feathers. The call of a raven is also a much deeper, croaking sound. In short, ravens look and sound sort of like “crows on steroids”. Unlike crows, which fly by mostly continuous flapping, ravens fly more hawk-like, with little flapping and more soaring along thermals. Ravens can be found throughout much of North America, ranging from Alaska, Canada, the Midwest to western region of the lower forty-eight states, and in Mexico. Subspecies are also found in Europe, Asia, and Africa. Mountain forests, boreal forests, and coastal cliffs are the primary habitat for these birds.  Image: www.alamy.com Image: www.alamy.com For those who may try to insult someone with the phrase “bird brained”, you may want to reconsider. Cognition refers to an animal’s ability to process information from its environment (ie: perception, memory, learning, decision making, and problem solving). High intelligence and problem solving skills are among the best traits of ravens. For example, most mammals encounter the concept of counting as a great challenge. Monkeys may take a prolonged training regime of up to 21,000 trials to learn to distinguish between different tones. Birds in general, master this much more easily. In controlled experiments, ravens can learn to count up to seven and ID a food box by counting objects in front of it with only a few trials. Although they are often solitary, ravens exhibit complex social systems with each other that help them to hunt cooperatively and communicate. Sub-adults frequently “recruit” other sub-adults to team up against adults in order to gain access to a carcass to scavenge from. Up to 100 allied birds may be recruited! Ravens will learn from others where to look for food and remember it for later. This type of behavior has been valuable knowledge for Inuit communities in finding caribou. Ravens follow wolves for a chance to scavenge off of a kill. Another interesting thing about ravens is their ability to play and create various social games similar to “Follow the Leader” by following others around or “King of the Mountain”, by trying to dominate a perch. They will also take turns manipulating and balancing sticks.  Odin and his two ravens, Huginn and Muninn. Image: galleryhip.com Odin and his two ravens, Huginn and Muninn. Image: galleryhip.com Ravens are common throughout the folklore of many different cultures. For Native Americans, they are often a symbol for a trickster in stories, or could even be an honored hero who displays faults. Along the Pacific northwestern coast, Raven was the creator of the world. In Celtic legends, ravens are seen as a foreboding omen of death due to their association with scavenging. They are believed to be powerful messengers between the realms of the living and the dead. The Norse god, Odin, was referred to as the “Raven God” from his connection to his two ravens Huginn and Muninn who flew around the world gathering information. Norse stories depict ravens as female figures called Valkyries who fly through battle, choosing who lives or dies. Whether in Westeros or Earth, ravens have played a noteworthy role in mythology. Their intelligence and resilient nature have aided in their survival during difficult environmental conditions, ranking them as a most impressive bird indeed. References

www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/common_raven/id Awoiaf.westeros.org/index.php/Raven Gill, F.B. (2007). Ornithology, 3rd ed. W.H. Freeman and Company, NY,NY. pp: 207-208, 322-323, 331, 500-501. www.transceltic.com/pan-celtic/ravens-celtic-and-norse-mythology National Geographic Field Guide to the Birds of North America, 4th ed. National Geographic Society. pp: 318 www.native-languages.org/legends-raven.htm Peterson, R.T. (2002). Peterson Field Guides: Birds of Eastern and Central North America, 5th ed. Houghton Mifflin Company, NY, NY. pp: 252

Image: lotr.wikia.com Image: lotr.wikia.com Leave it to the mighty elven king of the Woodland realm to enter battle in style - not on some robust destrier, but on an enormous, graceful elk. Although King Thranduil’s mount is not specified in the book, the film adaptions use a giant elk as the elven king’s war steed. The elk can be seen in the prologue of The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey and during The Hobbit: The Battle of the Five Armies as Thranduil’s method of transportation. Throughout the final battle, the elk aided in fighting off the orcs by kicking, and using its huge antlers to crush and fling the enemy. Incredibly, this massive elk existed outside of Middle-earth. In fact, despite its common name (Irish elk), it was not actually an elk, but was the largest species of deer to have ever lived. Standing at 2.1m (7ft) at the shoulder, weighing around 680kg (1500lbs), and having an antler spread of up to 3.9m (13ft), the Megaloceros giganteus was a formidable herbivore. Through the Pleistocene and into the early Holocene epochs, 2,000 years after the extinction of other megafauna 10,000 years ago, this animal persisted within grassland habitats. Although the first remains were found in peat bog deposits in Ireland, adding to the other part of the common name, Irish elk ranged all over Europe, N. Asia, N. Africa, and Siberia. A similar species was even found in China.  Image: www.geology.ohio-state.edu/~vonfrese/gs100/lect33/ Image: www.geology.ohio-state.edu/~vonfrese/gs100/lect33/ Why the ridiculously enormous antlers? As with the antlered or horned species of today, the antlers of the Irish elk were probably used in combat between males to show off their strength to earn breeding rights with females. Another possibility is that the antlers were a visual display for sexual selection. The antlers face forward, showing maximum surface area. This would signal to the ladies, “Look how impressive my antlers are! Aren’t I such a stud?” If they were used for sexual selection, then the larger, stronger antlers would become a favored trait among males, which would then continue to be passed on to offspring. When it came to selecting a war mount, Thranduil chose wisely. Other than the ability to crush orcs, those powerful, scooping antlers would have been an excellent set of weapons in defense against predators as well. If that did not work, the skeleton of the Irish elk indicates that the animal was an endurance runner. Therefore, it could out pace even the swiftest carnivores.  Photo: Fallow deer, www.dreamstime.com Photo: Fallow deer, www.dreamstime.com An analysis of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) places Irish elk within the “Old World deer” family, and in the subfamily Cervinae. Its closest living relatives today are the fallow deer species (Dama dama and D. mesopotamica), red deer (Cervus elaphus), and wapiti (C. canadensis). The fallow deer, however, have the most common characteristics which links the ancient deer more to the Dama clad. There are 2 points on the antlers, 1 point on the skull, 2 dental characteristics, 1 key similarity in the vertebrae and 2 limb-bone related traits that are shared between Irish elk and fallow deer. Another trait that the deer share is an enlarged larynx, or a “swollen Adam’s apple”. From these characteristics, fallow deer are considered to be the last representatives of this unique deer group. There are a couple main theories on why this large deer went extinct. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the most common theory was due to orthogenesis. Orthogenesis is the result of a change in some sort of internal trend within a lineage, as opposed to natural selection. In the case of the Irish elk, it was believed that the evolution of such massive antlers as a favorable trait was the animal’s downfall, because it was unable to support the weight on its head or avoid entanglement through forests. The second extinction theory is that the animal could not adapt to the environmental changes from the receding ice. It simply lost its habitat. Without a place to live, there were no resources to live on, and so ends the Irish elk. References Gonzolez, S., Kitchener, A.C. & Lister, A.M. (2000). Survival of the Irish elk into the Holocene. Nature, 405(6788): 753-754. Stewart, W. (2015). Giant Prehistoric Deer Lived 2,000 years after ‘Extinction’: Population of Irish Elk Thrived in Siberia after the Ice Age. www.dailymail.co.uk/ Lister, A.M., Edwards, C.J., Nock, D.A.W., Bunce, M., van Pijlen, I.A., Bradley, D.G., Thomas, M.G. & Barnes, I. (2005). The Phylogenic position of the ‘giant deer’ Magaloceros giganteus. Nature, 438(8): 850-853. Lotr.wikia.com/wiki/Thranduil’s_elk Pitra, C., Fickel, J., Meijaard, E. & Groves, C. (2004). Evolution and phylogeny of old world deer. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 33: 880-895. www.amnh.org www.ucmp.berkeley.edu www.bbc.co.uk/nature/life/irish-elk

Researchers take advantage of photography technology developed by the U.S. Army to capture beautiful portraits of bees native to North America.

Los investigadores aprovechan la tecnología fotográfica desarrollada por el ejército estadounidense para capturar hermosos retratos de abejas nativas de América del Norte. Read more Photography by Sam Droege, USGS |

Blog Archive

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed